To make it big in Africa, a business must succeed in Nigeria, the continent’s largest market. No one said it would be

IN 2001 MTN, a fledgling telecoms company from South Africa, paid $285m for one of four mobile licences sold at auction by the government of Nigeria. Observers thought its board was bonkers. Nigeria had spent most of the previous four decades under military rule. The country was rich in oil reserves but otherwise desperately poor. Its infrastructure was crumbling. The state phone company had taken a century to amass a few hundred thousand customers from a population of 120m. The business climate was scarcely stable.

MTN took a punt anyway. The firm’s boss called up colleagues from his old days in pay-television and found they had 10m Nigerian customers. He reasoned that if they could afford pay-tv they could stump up for a mobile phone. Within five years MTN had 32m customers. The company now operates across Africa and the Middle East. But Nigeria was its making and remains its biggest single source of profits

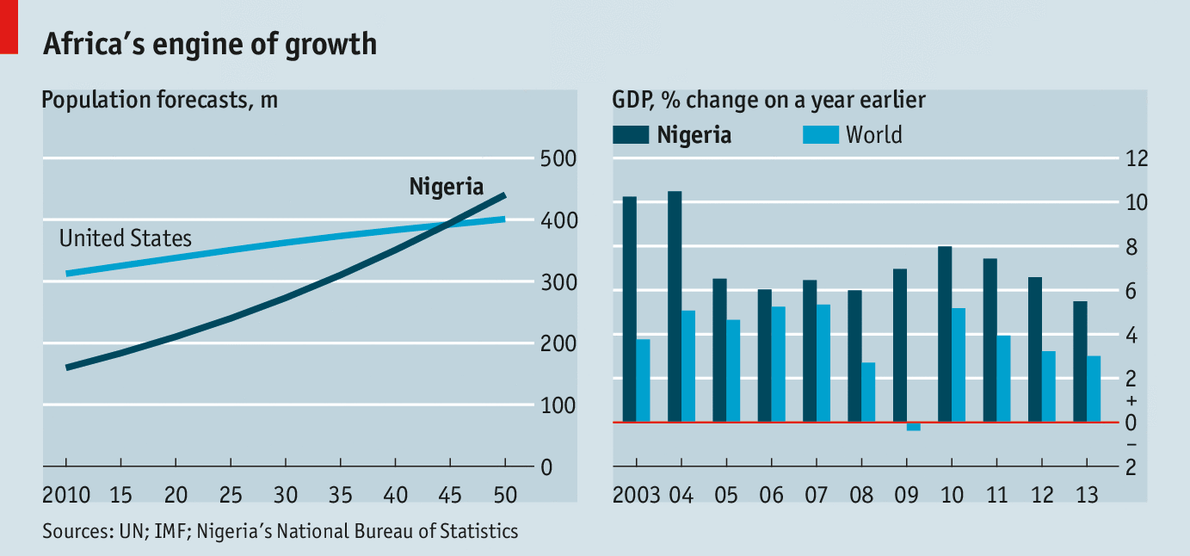

Tales of rich rewards have many firms scrambling to invest in Nigeria. Africa contains some of the world’s fastest-growing economies. Nigeria is the largest. In April its official GDP figures were revised up by 90% after hopelessly dated numbers were rebased. Roughly one in five of Sub-Saharan Africa’s 930m people lives there.

Nigeria’s promise has made it a test-bed for the Africa strategies of consumer-goods firms. This is not only because of its size. It is also because of the spread of Nigerian culture—its music and movies—around Africa, says Yaw Nsarkoh of Unilever. The Anglo-Dutch company has been trading in Nigeria for nearly a century and is expanding its operations. Nestlé, a Swiss rival, plans to triple sales over the next decade. Procter & Gamble, another global consumer giant, has just completed a factory near Lagos, its second in Nigeria. SABMiller, the world’s second-largest beermaker, built a state-of-the-art brewery in Onitsha, in the Niger Delta, in 2012 and is already adding capacity.

Just as Nigeria is used as shorthand for the business opportunity in Africa it is also a summary of the continent’s shortcomings. An outbreak of Ebola in Guinea has spread to Lagos. Attacks by Boko Haram, a fanatical Islamist group, are a chilling reminder that conflict is never far away in Africa. Transport and power infrastructure is poor. The rules of the game for business can change quickly and for the worse. Reaching a mass of consumers is no small task because most shopping is done in

open markets or at roadside stalls. Yet a growing band of global firms believes the business opportunity in Nigeria will outweigh the risks.

A shortage of electricity is one of the worst problems. Power cuts are frequent. Nigeria is ranked 185th out of 189 countries for ease of getting electricity in the World Bank’s “Doing Business” survey. Its power stations generate just 4GW of electricity, a tenth of the capacity in South Africa, the continent’s second-largest economy, which itself faces shortages.

Cross-border trade has been growing faster than GDP. Container traffic has risen by an annual average of 12% in recent years, says Toon Pierre of Maersk, a Danish shipping company. The creaking transport infrastructure struggles to cope. Nigeria has no deepwater port so can only accommodate vessels a quarter the size of the world’s largest ships. The paperwork at customs is voluminous. Shoprite, a supermarket chain based in South Africa, said last year that it can take 117 days for stock to reach stores in Nigeria. The time spent waiting for clearance leaves cornflakes tasting of detergent.

Things (sometimes) fall apart

Lagos’s two ports are close to the gridlocked city centre. The congestion is as bad inside the docks as around them. Sending goods by road is perilous. The biggest headache for Jumia, an online retailer, is not that its delivery vans will be robbed, but that they will be involved in an accident, says Jeremy Hodara, one of the firm’s co-founders. Nigeria has one of the world’s highest rates of road deaths. The government only recently made lessons and tests mandatory for new drivers.

Few countries make it as difficult to register property. Land is expensive and disputes over title are common. Piecing together tracts that are big enough for factories, warehouses or shopping malls is tricky. It costs more than twice as much to build a mall as in South Africa. Imports of cement are banned to protect local manufacturers. Dangote Cement, the biggest producer, makes a whopping 62% margin on sales in Nigeria.

The high cost of construction and land disputes have curbed the growth of formal retailing. Grocery chains account for less than 3% of retail sales. Shoprite reckons there will be room for up to 800 of its shops in Nigeria but as yet has only ten. No chain has a nationwide presence. Lagos is home to 20m people but can boast only two world-class shopping malls: the Palms, which opened in 2005, and Ikeja Mall, in 2011. Typically 40% of mall tenants are clothes retailers, says Michael Chu’di Ejekam of Actis, the private-equity firm that built them. A ban until 2010 on the import of finished textiles (a clumsy attempt to revive local industry) made developers think twice.

In such a fragmented market it is difficult to forecast sales. Transport bottlenecks make supply erratic. So consumer businesses are obliged to keep plenty of stock in reserve. Fresh bread is a draw to Shoprite’s stores, so it keeps a warehouse full of flour to ensure a constant supply, says Dianna Games of the South Africa-Nigeria Chamber of Commerce. Lean manufacturing is a non-starter. PZ Cussons, the British firm behind Imperial Leather soap, keeps up to three months of stock at its factories in Nigeria. In contrast the liquid-soap plant near its Manchester headquarters carries inputs to keep it going for just four hours, plus a few lorry-loads of finished goods.

Back to basics

Dispersed customers and inefficient supply chains increase the cost of doing business. That gives rise to the basic challenge for consumer-goods firms: how to sell to a mostly poor population at prices that are by necessity above global norms.

“You start by asking what consumers can pay,” says Unilever’s Mr Nsarkoh. “You then ask: ‘how can we supply at that price?’ ” Manufacturers aim for price points of 10 or 20 naira (6 or 12 cents) that are a gateway to low-income shoppers. The trick is to find a serving that is big enough not to be absurd but small enough to make those prices profitable: a 4g stock cube, say, or 26g of detergent, or 13g of toothpaste.

Newer entrants are pushing prices down. SABMiller’s Hero lager was launched in 2012 for 150 naira a bottle, compared with 200 naira for Star, the market leader and 250 naira for Guinness. It also offers chibuku, an even cheaper brew developed in Zambia. UAC Foods, a local firm, has not increased the price of its Gala sausage rolls since 2006, says Robyn Collins of Renaissance Capital, an investment bank. The price of Nestlé’s Maggi stock cubes is stuck at three for 10 naira. When the cost of inputs rises, it is pack sizes that usually adjust.

A second big challenge is getting goods to customers. “It is not just the poor roads in remote areas; it is also the variety of languages,” says Kais Marzouki of Nestlé, which delivers directly to shops in other emerging markets but in Nigeria opts to use third-party distributors instead. PZ Cussons has a network of 25 cash-and-carry depots dotted around Nigeria. Traders bring a lorry and stop off at separate warehouses to collect each category of goods. Fierce competition among traders keeps their markup as low as 1-2%, says Brandon Leigh, PZ’s chief financial officer.

Companies also use clusters of retailers who act as wholesalers to get to their customers. SABMiller’s brewery in Onitsha sells some of its output through the local beer market where small traders can buy lager by the case. Many of the phones and computers sold in West Africa pass through a warren of shops in Lagos known as Computer Village. Every corner of the district has been turned into an electronics outlet. Some shops are so narrow that customers have to walk in sideways.

One manufacturer chose to develop its own sales channel. “With our own retail chain we could be sure there would be an outlet for our brands,” says Pawan Sharma, who runs the Nigerian consumer-goods businesses of Tolaram, a Singaporean conglomerate. Its retail arm, called BestChoice, first rents shops and then invites shopkeepers to run them. It makes a profit on the stock it bulk-buys from manufacturers and sells at higher prices to its franchisees.

Three lessons emerge for outsiders doing business in Nigeria. First, be even more careful than usual about your choice of partner. The biggest error a business can make, says a senior executive at a big consumer-goods firm, is to pick an incompetent or dishonest distributor. Even arrangements with a sound local firm can fail if the incentives are wrong. Nando’s, a South African grilled-chicken chain, chose UAC Restaurants, part of a Nigerian conglomerate, to run its franchise, even though UAC owned a fast-growing rival chain, Mr Biggs

The idea of growing through acquisitions needs to be treated with considerable caution. SABMiller succeeded in other African markets by buying cheap but broken-down breweries and fixing them up. Its purchase of a defunct Nigerian firm also looked a sweet deal. But it soon faced claims for back-pay and unpaid invoices. Its next investment was a brand-new brewery. There are businesses in Nigeria with a solid heritage but it is easy to overpay for them. Tiger Brands, a South African food company, recently wrote off $80m from the value of Dangote Flour, a Nigerian firm it had acquired just two years earlier.

A second error is to assume that a model that works elsewhere will be successful in Nigeria. Woolworths, a South African clothing and food retailer, closed its three shops in Nigeria after less than two years, citing high rents and complex supply-chains as reasons. These problems aside, the firm made too little effort to promote its brand or adapt its wares to local demand. The retailer relied on the changing seasons to boost turnover for clothes but Nigeria’s clothing market had no such natural churn. It is hot all year round.

The third mistake is to run a Nigerian business by remote control. Companies do well by becoming Nigerian. Guinness, brewed in Lagos since the 1960s, has been adopted as a Nigerian brand (only Britain drinks more of the stuff). Nestlé, Unilever and PZ Cussons have been in Nigeria for yonks and have strong local identities. These businesses give power to local managers so they can adapt to shifting conditions, says Ms Games. The success of Shoprite in Nigeria is in part a result of constant tweaks to its supply chain.

If you can make it there…

As understanding of the Nigerian market improves and competition drives down costs, the reach of big consumer-goods brands is likely to increase. Most firms are betting that their revenues will grow faster than GDP. Nestlé’s aim to triple sales volumes in ten years would require it to grow by around 11% a year. Better business conditions will help. The recent privatisation of electricity generation and distribution should bring more reliable power supplies. Bottlenecks at ports may also ease. There is a push to complete a deep-sea port away from Lagos’s congested city centre by 2018 or 2019, says Mr Pierre of Maersk.

In some ways African markets can leapfrog economies that developed earlier. Thirteen years after MTN won its licence, there are now around 115m mobile phones in use in Nigeria. Access to the internet—and thus to online retailers—is growing rapidly. Jumia has found that each personal computer from which online orders are made is linked to many account holders. It implies that the firm’s potential market is “not just someone with a PC but someone who knows someone”, says Mr Hodara. The pool of online shoppers will deepen as smartphones become cheaper.

Nigeria’s population is likely to overtake America’s by 2045, according to projections by the United Nations. Some firms are already preparing the ground. Unilever is trying out a scheme it developed in India to reach remote markets. It employs as local agents women who understand the area’s languages, customs and social networks. It is also working to bring more of its suppliers into Nigeria to cut freight costs.

The pace of formal retail development, though slow, is picking up, as money for African malls floods into private-equity and property funds. It is likely that in the next two years at least 200,000 square metres of retail space will be completed in Lagos, Abuja and other Nigerian cities, says Leonard Michau of Broll, a South African property firm. That is the equivalent of ten malls the size of Ikeja or the Palms.

Yet such is the growth in consumer demand that it is unlikely shop-building will keep pace. So e-commerce is likely to grab a bigger share of sales in Nigeria than in richer economies. Jumia is in eight African markets, having recently expanded into three new ones. It has been in Nigeria only two years but the country is crucial to its success because it provides the scale Jumia needs. It is also the best testing ground for new ventures, says Mr Hodara. “If it works in Nigeria, you can do it anywhere.”